General election briefing: reindustrialising and rebalancing the UK economy

Centre for Progressive Policy general election briefing

20 June 2024

13 minute read

- Increasing manufacturing – in the parts of the UK where that’s feasible – can bring better paying jobs to a wider range of workers in some of the country’s poorest places.

- Manufacturing should be a focus of the next government’s industrial strategy, alongside a plan to deliver good jobs in the service sector (especially social care and retail).

- To get there, CPP is calling for a new UK Manufacturing Mission - with manufacturing rising as a share of output and employment over the next parliament.

- CPP also calls for a number of reforms to rebuild our technical skills system, and for the establishment of Regional Co-Investment Funds to catalyse higher public and private investment.

Earlier this year, the US economist Tyler Cowen set out on his blog what he believes are the five causes of the UK growth shortfall.

Taking the top spot, which Cowen attributed 50% of the total shortfall to, is that the “UK economy does not specialise in making things that either foreigners or its own citizens want to buy.” Trends in global consumption have largely moved beyond the UK’s comparative advantages, he suggests, and the UK has struggled to diversity into industries with higher global demand.

Cowen’s reading of the UK’s growth shortfall reflects a view held widely across the population that “Britain doesn’t make anything anymore.” The true picture is, of course, more complex.

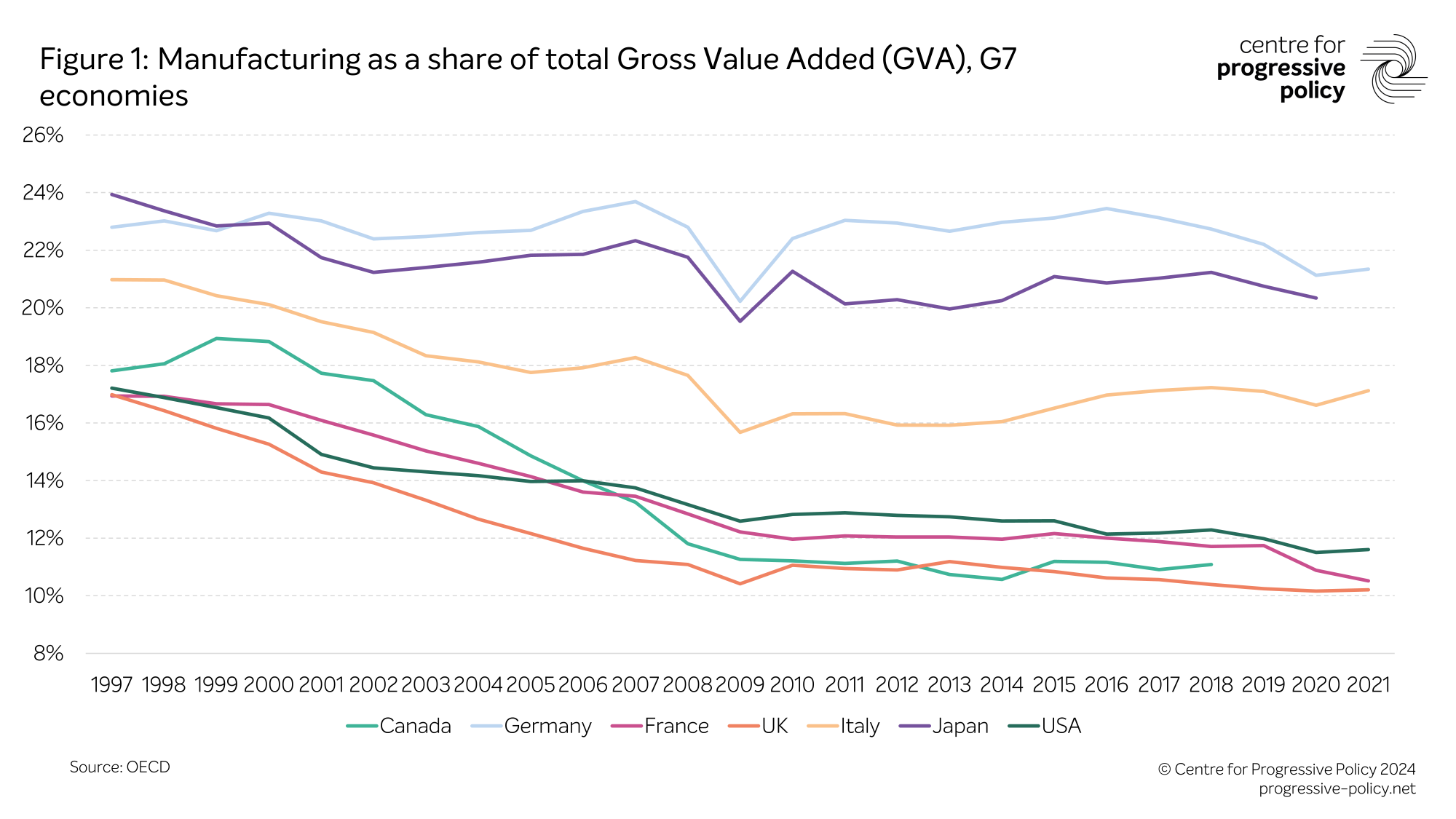

Mostly, what the UK now exports to the rest of the world is services - we are the second largest exporter of services in the world, with service industries accounting for 80% of our national output. It is true, also, that manufacturing output is low in the UK relative to our peer nations, being the lowest in the G7 and lower than the OECD average. UK manufacturing today is smaller as a share of total national research and development (R&D) expenditure, exports, output, and employment, than it was in 1997.

The strength of the UK’s service sector is not a problem (or rather, it is a problem that most of the world would love to have), and we must continue to build our strengths in service industries and ensure that they provide good jobs.

However, there are also good reasons why we should seek to “reindustrialise” the UK economy if we want a more inclusive economy:

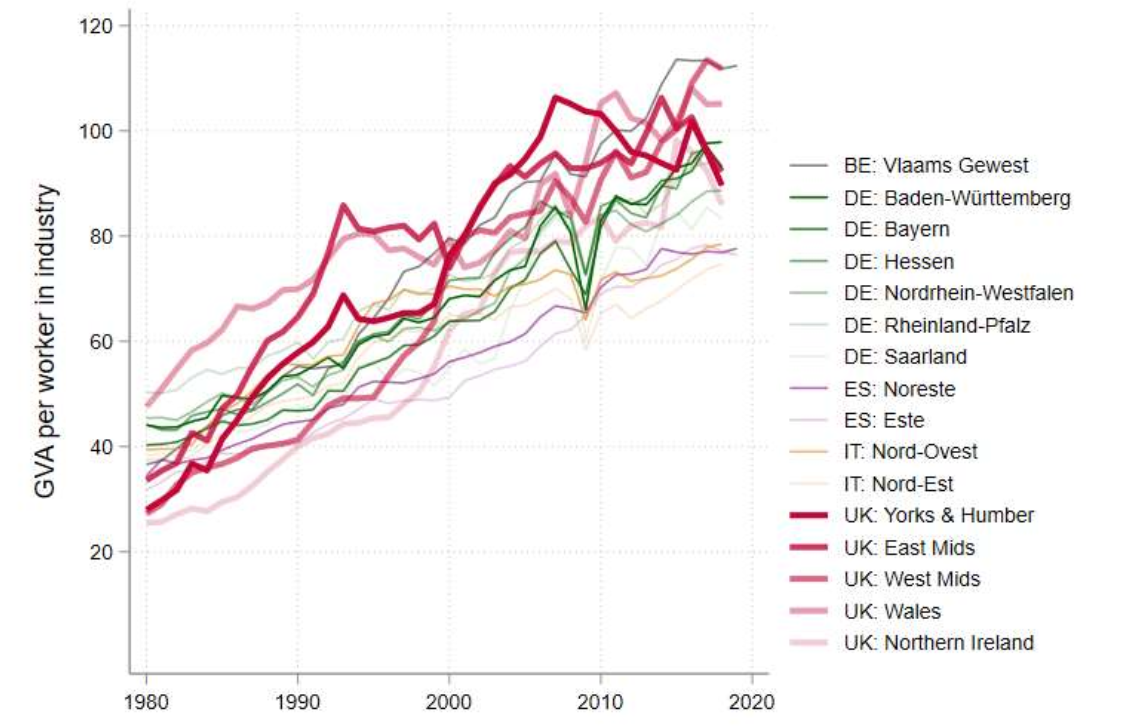

- UK manufacturing is highly productive, and offers a wider range of highly paying jobs to those with low- or mid-level skills: Manufacturing productivity continued to rise while it has declined as a share of both employment and output – Figure 2 shows how manufacturing productivity in British regions is higher than the most industrialised regions of Western Europe (such as the Rhineland and northern Italy)

- Manufacturing matters for the vibrancy of the whole economy, protecting all jobs: Manufacturing sectors have typically higher-than-average productivity. As a result, slowdowns in manufacturing productivity (or manufacturing’s share of output) feed through to aggregate productivity slowdown across the whole economy.

- For many lagging areas, manufacturing growth provides opportunities for better work: Many of the future growth opportunities in service industries for poorer areas of the country are in low productivity, low earning services. CPP analysis suggests many such areas possess pockets of high-productivity, high earning, and high employing manufacturing clusters.

Figure 2: Industry productivity in Western Europe’s 16 most industrialised regions in 1980

The argument for a “reindustrialisation” of the UK economy is not new. There has been much talk about rebuilding the UK’s industrial capacity and rebalancing the economy over successive decades. But efforts to generate productivity growth outside of London and the South East have run up against three particularly binding constraints:

- Weak public infrastructure: The UK’s public infrastructure (particularly transport), is weak, disjointed, and underinvested in. This stifles productivity growth mainly through limiting the mobility of workers to access good jobs, which reduces the effective size of local economies, limiting the agglomeration benefits of clustering. Fewer than 1% of South Yorkshire’s population live within a 30-minute public transport journey to its Advanced Manufacturing Park.

- A dysfunctional planning system: Infrastructure of all kinds is more expensive to build in the UK. Our internationally-unusual discretionary planning system creates uncertainty. This in turn adds major costs, delays, and empowers vested interests to veto the development of housing, critical economic and social infrastructure, and business premises. The 360,000 page planning application for the Lower Thames Crossing, which cost nearly £300m, would be five times longer than the crossing itself if it was laid end to end.

- Technical skills shortages: Over a third of job vacancies are due to technical skills shortages, with some of the most acute shortages being in priority growth sectors (the current “green skills gap” is estimated to be around 200,000 workers). Many of these shortages are more acute at the local level, and there is similarly a lack of demand for technically skilled workers in many regions (from STEM apprenticeships through to post-docs).

The main political parties’ manifestos all contain – implicitly or explicitly – a vision for supporting the UK’s domestic manufacturing strengths and growing high value industries.

The Conservatives have dropped the term “industrial strategy” altogether, but their manifesto sets out plans for expanded licenses for clean energy; and a big increase in domestic defence manufacturing as part of an expansion of military spending. Their model focuses on raising public spending in priority areas, rather than “market-making”.

Labour’s proposals are far more detailed and focus on a more active role for the state. They have committed to reestablishing the Industrial Strategy Council on a statutory footing. The bulk of their public investment plans have been committed to green industries, in the form of a new £7.3bn National Wealth Fund, and a new state-owned energy company, Great British Energy, endowed with £8.3bn over the next parliament. New ten-year Local Growth Plans for Mayoral Combined Authorities will coincide with further devolution of transport, adult education and skills, housing and planning, and employment support.1 This will be complemented by a new ten-year infrastructure strategy, ten-year R&D budgets, liberalisation of the planning system, and giving the British Business Bank a stronger mandate to invest across regions and nations.

Labour’s industrial plans are heavily centred around physical capital, with a glaring omission on human capital. Labour has committed to forming a new body, Skills England, yet its remit, and where it sits within the wider skills system, remain largely undefined. The Liberal Democrats and the Greens both have bolder offers on skills – the Liberal Democrats would give every adult £5000 for education and training, while the Greens have pledged a £12.4bn skills package with £4bn earmarked to support workers through the green transition.

If, as the polls suggest, Labour are on course to form a majority government, they will inherit an economy characterised by stagnation and low levels of business investment.

Many local and regional authorities are already leading the way on how to develop coherent industrial strategies to foster inclusive growth, including Greater Manchester and the West Midlands. Greater Manchester was the first major Combined Authority to adopt a Good Employment Charter as part of its industrial strategy – seeking to translate improvements in productivity into job quality across all sectors, including “foundational economy” industries such as health, social care and retail. West Midlands has leaned heavily into inclusive growth as its guiding principle for the region’s economy development – setting out in its plan the different levers it possesses and how they can be pulled to harness inclusive growth and the development of clusters in frontier sectors such as automotive manufacturing, aerospace, and life sciences.

Many local authorities have also used their discretionary power to develop effective schemes to support people into good jobs. Belfast’s Employment Academy Scheme, for instance, is one initiative that could be scaled up nationally to help reduce technical skills shortages and widen access to employment opportunities. It is intentionally flexible to different life demands and circumstances – providing resources for childcare, travel, and subsistence, should they be barriers to accessing the scheme. The scheme is intentionally designed to address acute employment shortages (recently, for example, for HGV drivers), as well as delivering intensive skills training courses to support workers into frontier sectors.

1. A UK Manufacturing Mission

Labour has embraced economist Mariana Mazzucato’s “mission-driven government” principle wholeheartedly with their “five missions to rebuild Britain”. The first mission is to “secure the highest sustained growth in the G7.”

If elected, Labour should introduce a UK manufacturing ‘sub-mission’ to underpin this, that would seek to raise the manufacturing sector’s share of GDP and employment over the next parliament. It should focus on growing high-value-add manufacturing clusters, boosting the adoption of new and green technologies and increasing manufacturing R&D investment, with a strategic focus on reaching poorer and underperforming areas.

CPP has set out a remit for a UK Manufacturing Mission here.

2. A new network of Regional Co-Investment Funds to meet this Manufacturing Mission

We will need to do more to incentivise higher levels of private and public investment to develop our industrial capacity. This will require new institutional architecture as well as new ways of working between institutions, as part of a cohesive “mission framework”.

To achieve this, the next government should establish a new network of Regional Co-Investment Funds across the UK, built out of collaboration between the British Business Bank, the UK Infrastructure Bank, local government, and private lenders. Local leaders should sit on the boards of these funds.

CPP has set out a full remit for a network of Regional Co-Investment Funds here.

3. Reforming and rebuilding capacity in our technical skills system

Any efforts to nurture high-value industries will be constrained so long as there are shortages of skilled, technical workers – with STEM skills at all levels, from apprenticeships to graduates – to fill vacancies.

Recent CPP research found that the geographic distribution of potential labour supply for green jobs is highly unequal, suggesting that for many areas there are currently hard limits on how far the green transition might drive economic growth.

To meet the high (and rising) demand for technical skills by ensuring more people can access training, we recommend:

- Expanding the new capital allowances scheme (known as full expensing) to include investment in skills and human capital development, for those without a level 4 qualification.

- Reforming the current ‘Right to Train’ by making it available to all employees who have worked for an employer for at least 26 weeks and introducing a new ‘Right to Retrain’ that removes the requirement for workers to undertake training only where it improves their performance in their current role.

More recommendations to rebuild capacity in our technical skills system can be found here:

- Centre for Progressive Policy (CPP), Open for Business: Unlocking investment in low-earning economies

- Centre for Progressive Policy (CPP), Are we ready? Navigating the green transition in an age of uncertainty

- Centre for Progressive Policy (CPP), How to create good jobs in England’s towns

- Centre for Progressive Policy (CPP), Reskilling for recovery

The UK has room to expand well-paying, productive work in manufacturing: if we can address our weak public infrastructure, dysfunctional planning system, and reduce technical skills shortages.

But for large swathes of the population that alone will not be enough. Even if we can check and reverse the historic decline in manufacturing employment, it will never employ the same numbers as it did in the 1950s.

Instead, ‘reindustrialisation’ is just one part of the puzzle – albeit one that can provide good jobs and help the UK pay its way in the world – of building an inclusive economy. It needs to go alongside a strategy for good jobs, focused on our higher-volume service sector employers like social care, retail and hospitality.

In our next general election briefing, we will turn to that wider challenge of creating good jobs in sectors outside of manufacturing.