Maintaining momentum in skills devolution

7 September 2018

5 minute read

Towards the end of last year, England’s seven regional mayors came together to call for further devolution to their city regions. The intervention signalled their concern that devolution may have slipped down the political agenda, with key proponents such as George Osborne and Nick Timothy now out of the picture.

At the centre of the mayors’ demands were new powers on skills. Analysis undertaken by the Centre for Progressive Policy suggests they were right to do so, highlighting the widespread mismatch in the distribution of FE courses across subjects compared to the needs of businesses in many local areas. For example, in one combined authority area there is an estimated shortfall of up to 1,300 IT technician course completions relative to the needs of business each year. The reverse is true for sports and fitness courses, with a likely annual surplus of more than 800.

Unfortunately, under the national funding formula, colleges have little incentive to align their provision to local economic realities. Many are forced to prioritise more profitable courses simply to ensure their continued financial sustainability, even if they bear little relation to the kinds of skills businesses need.

From 2019/20, however, the regional mayors will have at their disposal the devolved Adult Education Budget (AEB). Effective use of the AEB should allow combined authorities to begin to influence the incentives facing learning providers and so improve the alignment of provision. The Greater London Authority (GLA) has already signalled its intention to move AEB funding towards a more outcomes-based approach. The new Skills for Londoners Strategy seeks to leverage outcomes-related funding to address London’s sectoral and occupational skills needs, an indication that this cannot be achieved using national funding formulas alone.

While devolving the AEB is a step in the right direction, given its relatively small size the mayors are right to push for more. As such, it is encouraging that on a recent visit to Dudley College the Education Secretary, Damian Hinds, announced a new £69 million ‘skills deal’ for the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA). The deal will support ‘more young people and adults into work as well as upskilling and retraining local people of all ages’.

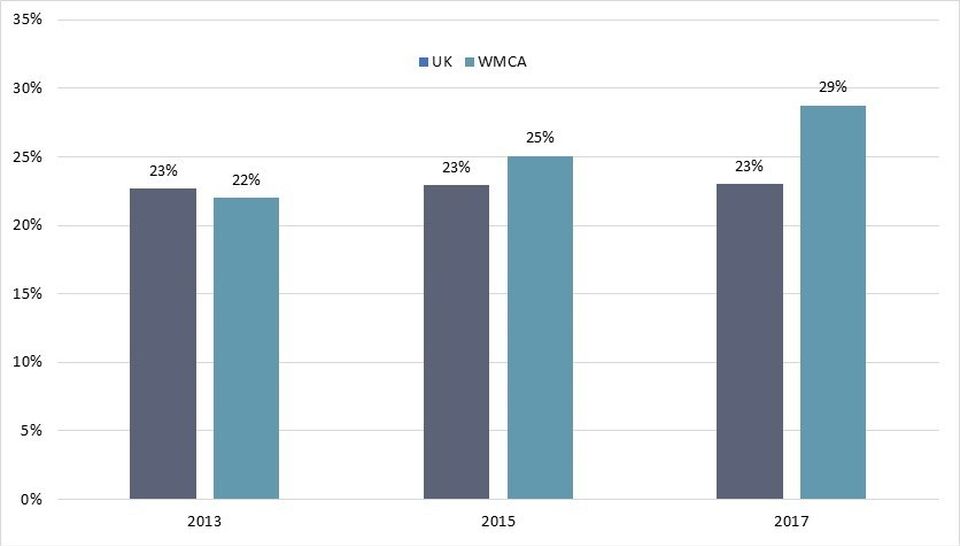

The WMCA is a good choice for the deal. Between 2013 and 2017 the area has moved from being just below the national average for skills shortages to being well above it. As shown in the below chart, employers struggled to fill almost three in every 10 vacancies in the West Midlands in 2017 due to a lack of appropriate skills among applicants. Two of WMCA’s three Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) areas performed particularly badly in this regard, with Greater Birmingham and Solihull and the Black Country featuring among the 10 worst performers in England for skills shortage density.

WMCA is also a good choice given its commitment to achieving inclusive growth, having recently established an Inclusive Growth Unit, of which the Centre for Progressive Policy is a partner. The skills deal could no doubt be a valuable delivery tool in this regard.

Chart 1: Density of skills-shortage vacancies, WMCA vs the UK, 2013-2017 [1]

The skills deal clearly adds to the WMCA’s policy arsenal, but, given the scale of the challenges facing combined authorities, it still does not go far enough. Data-driven, place-based co-commissioning of post-16 skills provision through fully-fledged devolved skills funds must be the ultimate objective, something that the current WMCA deal stops short of. Such skills funds could draw money from 16-19 technical education funding and any local underspend of the apprenticeship Levy, as proposed by Core Cities.

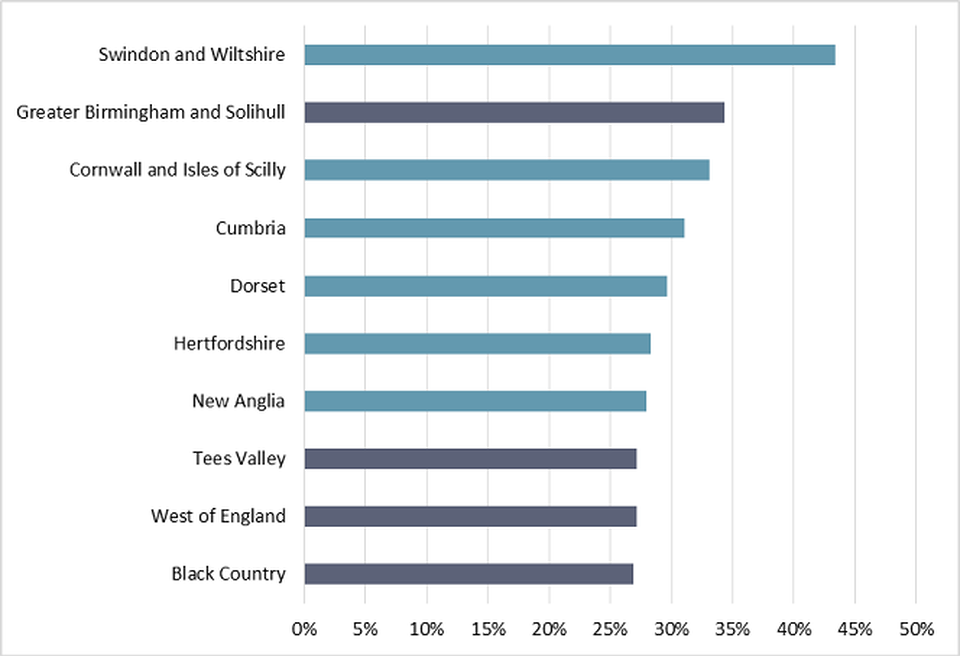

At the same time, we must also remember that combined authorities still only cover a relatively small area of the country. As shown in chart 2, six of the 10 LEPs with the highest skills shortage densities in 2017 are not currently in combined authority areas. For their part, LEPs are eagerly awaiting the introduction of the Shared Prosperity Fund that will follow the local industrial strategies. But it is unclear how much of this will be available for skills and it is not due to be introduced until 2021. In the long run, ensuring people from all parts of the country can benefit from place-based skills systems remains an important challenge.

Chart 2: LEPS with highest density of skills-shortage vacancies, 2017 [2]

Putting concerns about coverage aside, local and regional government must now capitalise on the momentum that is beginning to build. As the Mayor of Greater Manchester, Andy Burnham, said recently, ‘It is time to give us the tools we need to change the lives of the people we represent.’ The devolved AEB and the WMCA skills fund are no doubt positive developments. But skills devolution is a process, and if we want to build truly place-based skills systems then these must be just the start.

This blog was originally posted on Solace. You can follow Andy Norman @andynorman810

Notes

[1] Source: Employer Skills Surveys 2013, 2015, 2017.

[2] Source: Employer Skills Surveys 2017.