Diagnosis critical

Launching an inquiry into health and social care in England

5 June 2018

5 minute read

Marking the launch of the Centre of Progressive Policy’s inquiry into health and social care in England, our first report has identified two stark population inequalities which powerfully show why this work is needed.

Our new and independent analysis shows that:

17% of the population in England reside in 32 “risk zones”. These are local

authorities that are home to both below-average health outcomes and deficit-running NHS trusts. We have found that age-standardised mortality rates for

causes considered avoidable, amenable and preventable are 29% higher than in

other local authority areas.

6% of the population reside in 13 “crunch zones.” These are local authorities which have an elderly population weighing on an underfunded care sector, in turn compounding financial pressures on NHS trusts.

This report identifies some alarming trends that the current financial pressures have put on health and care services:

- Even if a trust improves its financial position by 10 percentage points the standards for elective care would still not be met, although this would make them likely to hit A&E and cancer treatment targets.

- If the average trust were to experience another 1,000 delayed transfers of care (DTOCs) on top its annual average of 1,680, its financial position could be expected to deteriorate by 25%.

- The places where people live contributes significantly to years of potential life lost, propensity to mood and anxiety disorders and unplanned admissions to hospital.

The report also explores four key questions to set the scope for our programme of work:

1. Is financial strain affecting constitutional standards of care?

Most NHS trusts are now running deficits with a negative effect on patient safety and on standards of cancer treatment, accident and emergency attendance, and elective care. But throwing more money at the NHS will not solve the problem. Neither will cutting costs or rationing, which cannot give universal access through an unsuitable and unsustainable healthcare system. We explore the extent to which there is a relationship with funding and quality of care.

2. What kind of system is needed to meet the needs of a changing population?

Neither hospitals nor social care settings are adequately set up to care for an ageing population. The current policy response is to integrate the two services, but CPP analysis shows that social care is placing additional strain on the NHS instead of relieving its pressure as it is also underfunded. Public expenditure on social care has declined by 8% since 2010 as central government cut local authority funding, saving it pennies locally but costing it pounds through the NHS. Local-authority fees for social care are on average 10% below the cost of provision.

3. What role for place in enabling healthy lives?

Social conditions, which account for up to 61% of a population’s health, also vary locally in a way that is not matched by variation in the provision of healthcare. This has created a number of ‘Risk Zones’ – localities where residents are hit first by a social environment that causes illness and then by a care system unable to cope with their illness. Avoidable deaths are 29% higher in Risk Zones than other localities. Social care is also highly fragmented locally both in terms of providers and funding, which does not always reflect local conditions. This has created a number of ‘Crunch Zones’ – localities whose populations are ageing faster than average and placing a greater than average strain on care systems.

4. How do we need to rethink health and social care funding models?

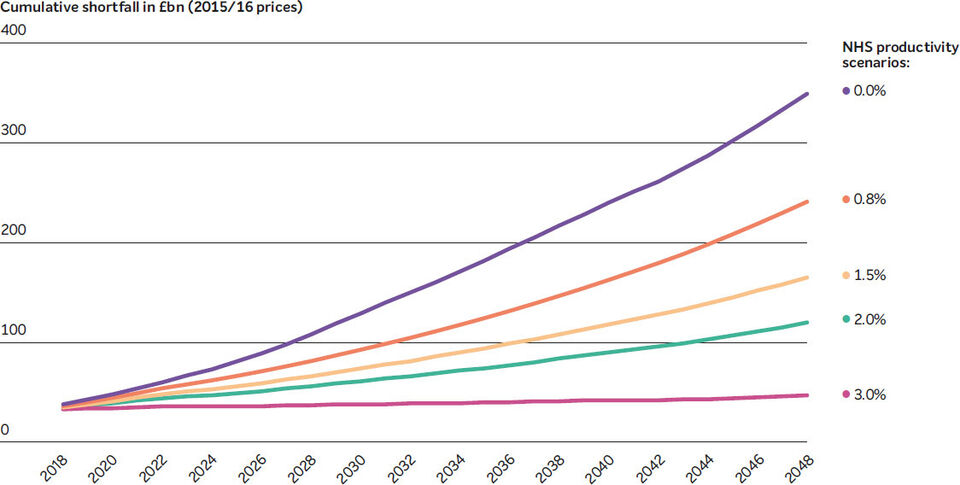

Without this root and branch reform, which will also require resources, CPP analysis shows that with the current set up of healthcare and social care the annual funding shortfall will cumulate to £241bn by 2048/49 under central assumptions of ageing, income growth, and medical costs. Closing the shortfall would require unseen rises in existing taxes – a nine-percentage point increase in the basic rate of income tax, for example. Alternative options, ranging from hypothecation to rationing, insurance, and technology, need to be assessed through public and professional deliberation.

To reorder funding priorities to match health’s social and demographic drivers, we must change the way we think about health more generally – from acute crisis and response, to the management of population health and the longer- term promotion of wellness that is grounded in wider economic and social interventions.

The NHS was one of the world’s first three national universal healthcare systems. It ranks highly on international measures of efficiency. But, creaking towards its 70th anniversary this year, the NHS is struggling to keep up that pioneering spirit when it is most needed. Partly because we hold the NHS so dear, and partly because every other day it is said to be in crisis, we forget that it is a radical, pioneering institution. It is with this radical ambition in mind that we will approach our programme of work.