Paternity leave, rewritten

CPP teams up with The Joseph Rowntree Foundation to explore what a better paternity leave offer could deliver for Britain.

30 April 2025

6 minute read

Britain’s paternity leave offer is meagre: two weeks, poorly paid, and inaccessible to many. The result is predictable. Take-up is low, particularly among those in precarious work or with lower incomes. Yet, a growing body of evidence suggests that this is a missed opportunity. Recognising the stakes, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) and the Centre for Progressive Policy (CPP) set out to ask a simple question: what would a better paternity leave system deliver for Britain - and why are MPs urging the Treasury to take it seriously?

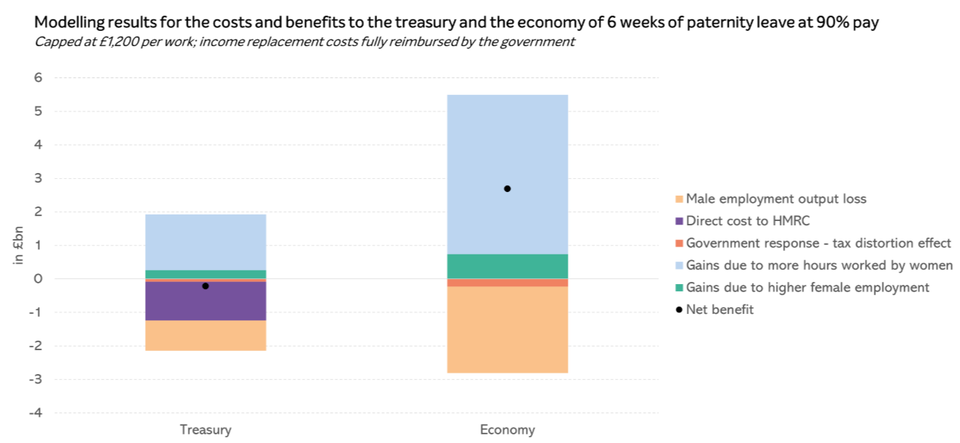

Drawing on evidence from 28 studies across 16 advanced economies, our new modelling finds that offering six weeks’ paternity leave at 90% of average earnings could deliver a net economic gain of £2.68bn per year. The reform is expected to generate £5.5bn in additional annual output from women—easily offsetting the £2.8bn lost while fathers are temporarily away from work. The net cost to the Treasury, once higher tax receipts are factored in: just £220m.

The primary driver of this gain is the increase in the number of hours worked by women, supported by more modest contributions from higher female labour market participation. Paternity leave is designed to get fathers more involved at home, giving mothers more time to invest in paid work. International evidence suggests this "direct effect" helps boost women's labour market engagement over time, contributing to broader economic gains—as reflected in our analysis.

And these gains are progressive. The biggest uplift is among lower- and middle-income households, where fathers are least likely to get enhanced leave through work. For the lowest earners, the net benefit is £580m. For the highest earners—many of whom already receive generous employer top-ups—the policy shows little additional effect, and in some cases, a small net cost.

Improving paternity leave could be an important step towards advancing gender equality. Lack of father-specific, well-paid, and protected leave reinforces the norm that caregiving is primarily a woman’s responsibility. Although broader cultural and economic forces also shape these patterns, the design of leave systems plays a crucial role in either challenging or entrenching them.

One key consequence of unequal caregiving is the motherhood penalty. The UK has one of the highest part-time pay penalties among advanced economies. This is driven in large part by occupational segregation between full- and part-time roles, with women far more likely than men to work part-time after having children. The consequences are well documented: women often slide down the occupational ladder when switching to part-time work, taking on lower-skilled, lower-paid jobs. Re-entering full-time work can be difficult, and earnings rarely recover. While the pay gap within specific occupations may be small, the shift into lower-quality roles results in significant income losses over time.

By boosting the number of hours worked by women—as evidenced by our model—enhanced paternity leave can help arrest this slide and begin to tackle the motherhood penalty head-on. CPP’s previous analysis of OECD data reinforces this. Countries offering more than six weeks of well-paid, reserved leave for fathers tend to have lower gender wage gaps as well as increased labour force participation when compared to those that don’t. In a context where these gaps are not just persistent but worsening, a modern, inclusive leave system is not a silver bullet, but it is a critical step in the right direction.

There is strong evidence that simply offering longer leave is not enough. The design of paternity policy is central to its impact, and two principles matter most. First, the leave must be generous enough to drive uptake—particularly among lower- and middle-income fathers. If generosity is too low, uptake is limited to higher earners who would likely have taken leave regardless, creating a deadweight cost without widening access or shifting behaviour. Crucially, it is only when more fathers take leave that the policy begins to generate gains in female labour force participation and working hours.

Second, the entitlement must be non-transferable. When couples are allowed to reallocate leave, it tends to remain under-used by fathers—especially where the man earns more. This is the core weakness of the UK’s Shared Parental Leave scheme: lightly paid, transferable, and used by just 5% of eligible fathers.

Enter the “daddy quota”. Norway’s introduction of non-transferable, well-paid leave for fathers in 1993 led to a sharp increase in uptake and lasting behavioural shifts. Fathers became more involved in caregiving, mothers returned to work sooner, and employers adapted—reporting improved productivity and normalising leave for both parents. Quebec and Sweden followed with similar models, achieving comparable results.

Britain’s current system lacks both the design—and the ambition—to produce these effects.

One thing is clear: expanding and enhancing paternity leave is far from a marginal reform. It is a high-impact policy with relatively low fiscal cost and wide-reaching economic and social returns. What’s more, the case is still understated. Our model focuses on labour market and fiscal outcomes, but it does not capture the long-term developmental benefits of fathers spending more time with their children. In this respect, the economic impact of better paternity leave is likely underestimated.

This is what makes the reform so compelling: it is not a trade-off between economic efficiency and social progress. It is one of the rare policies that delivers both.