General election briefing: the state of inclusive growth

Centre for Progressive Policy general election briefing

4 June 2024

12 minute read

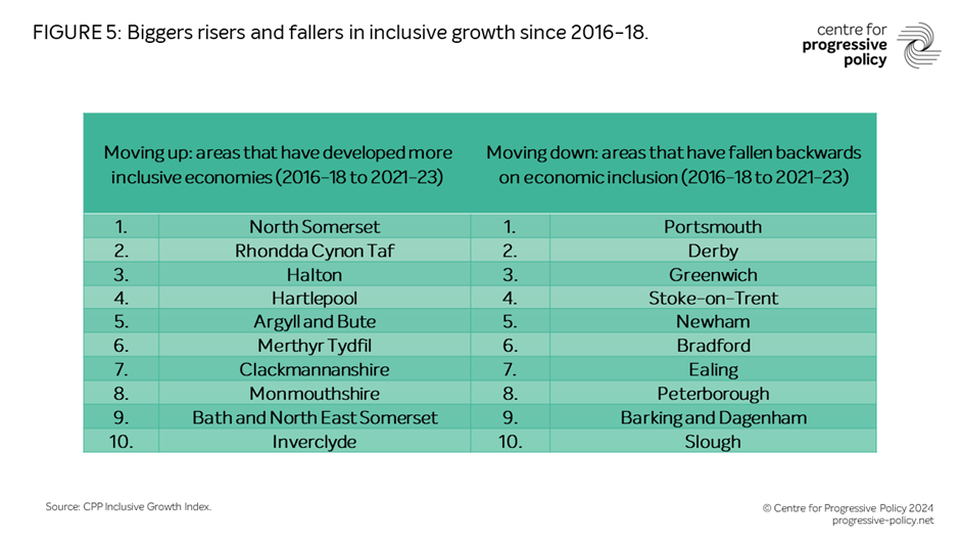

- At the end of the “levelling up” parliament, inclusive growth across the UK has barely shifted - with almost as many communities falling backwards as have moved forwards.

- While earnings inequality has fallen and earned income has risen in communities across the country, this has been offset in part by stagnating life expectancy and rising unemployment and inactivity.

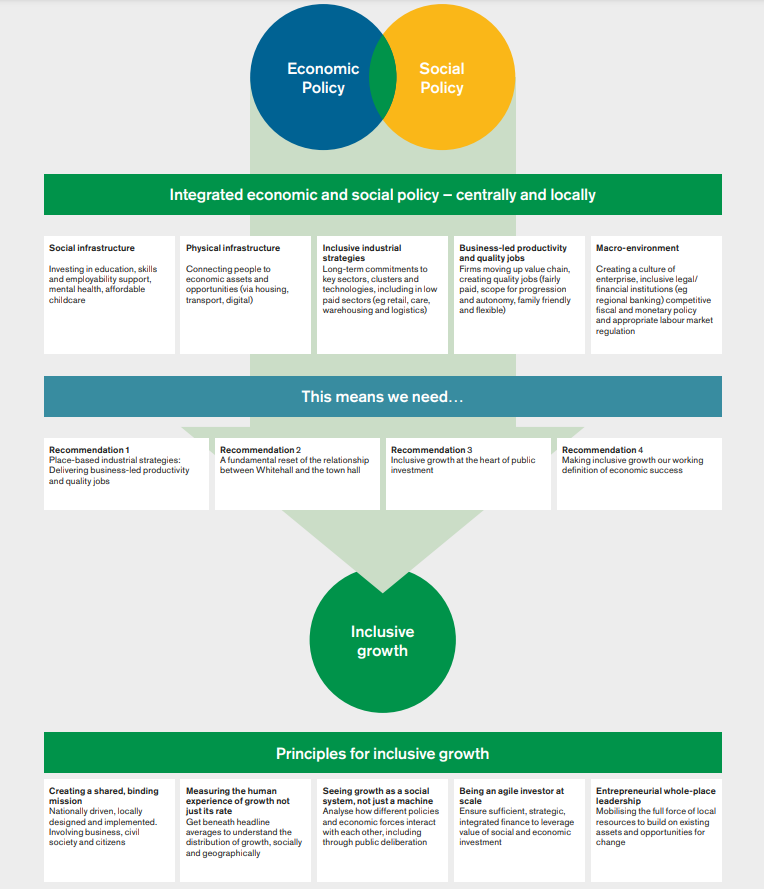

- The next Government needs to ask how we can make our economy work better for all people and places. The Centre for Progressive Policy’s work – into childcare, industrial strategy, and public services – points the way.

Both Labour and the Conservatives have used the first weeks of the general election campaign to set out a “safety first” message. Gone is the heady talk of a levelled up, Global Britain we saw on the campaign five years ago. In its place, we hear about economic security before growth, and growth before public investment.

Are we being offered a false choice between getting the economy going and fixing public services? Are there policies that can increase both efficiency and equity? And what is our wider vision for economic growth, to which politicians can put realism and rigour to service?

In this briefing, the first of a series in the run-up to the 2024 general election, the Centre for Progressive Policy (CPP) sets the scene as all the UK’s political parties try to answer that question.

At CPP, we bring together groundbreaking quantitative and qualitative research with the rich insights of practitioners - at local, regional, national and UK level, in all four nations, through our Inclusive Growth Network (IGN) - to identify ways for as many people as possible to contribute to, and benefit from, growth across the UK.

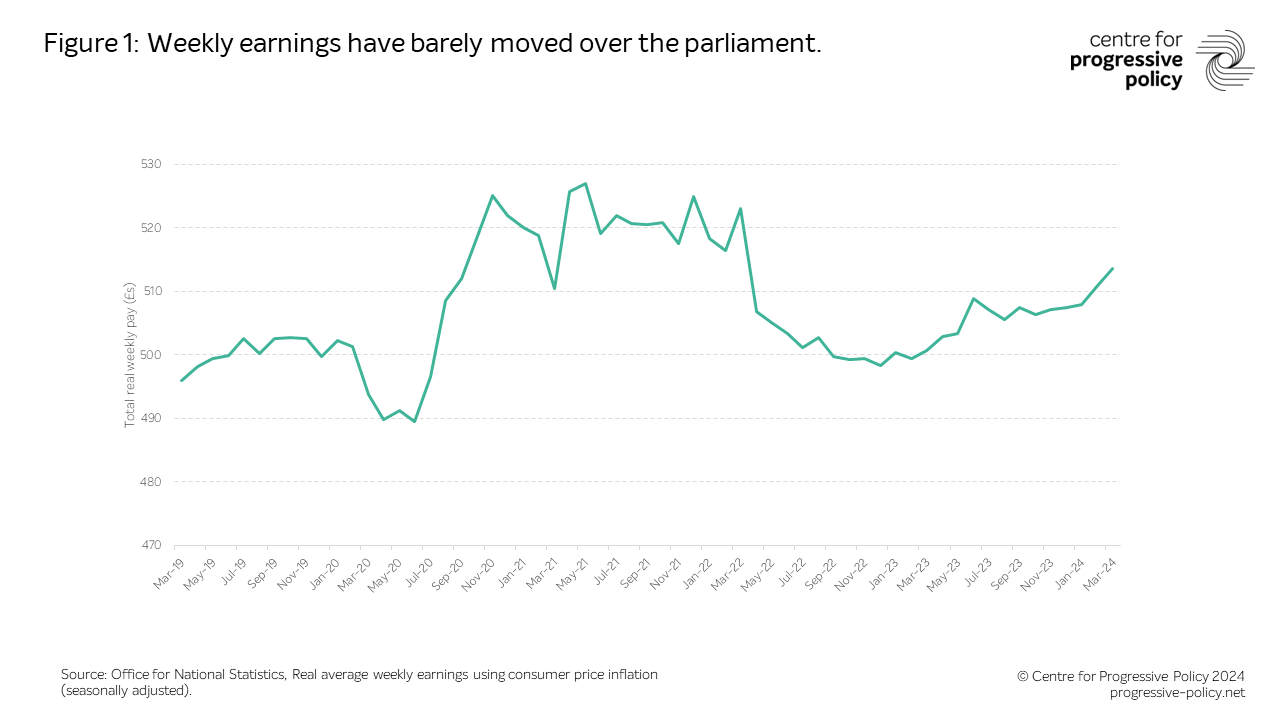

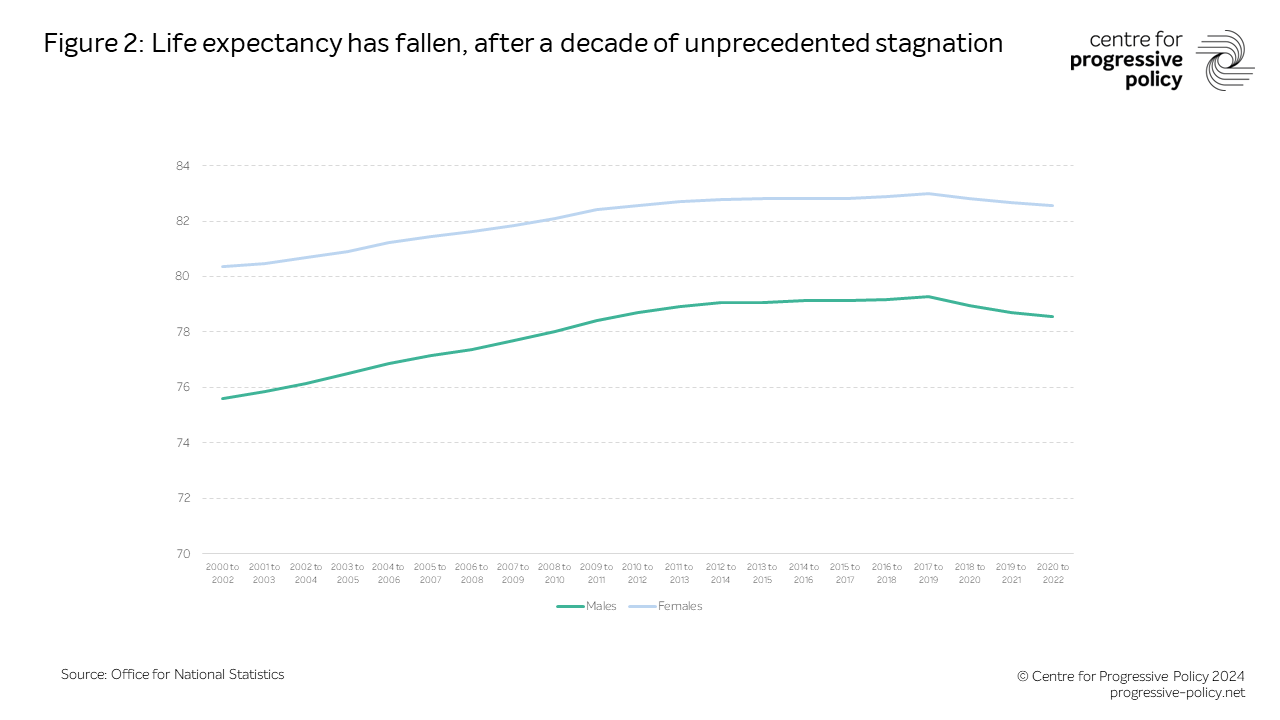

While the UK economy has been stagnating for the fifteen years that followed the global financial crisis, the most recent parliamentary cycle – characterised by the COVID-19 pandemic and cost of living crisis – has been particularly turbulent. Since 2019, we’ve seen pay barely shift, life expectancy fall, and economic inactivity rise.

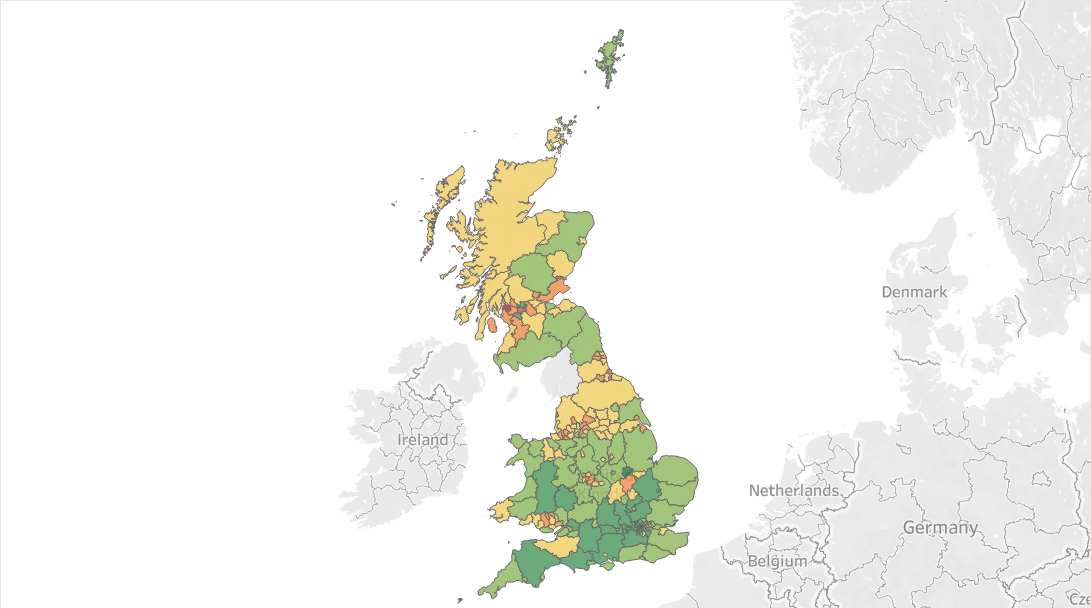

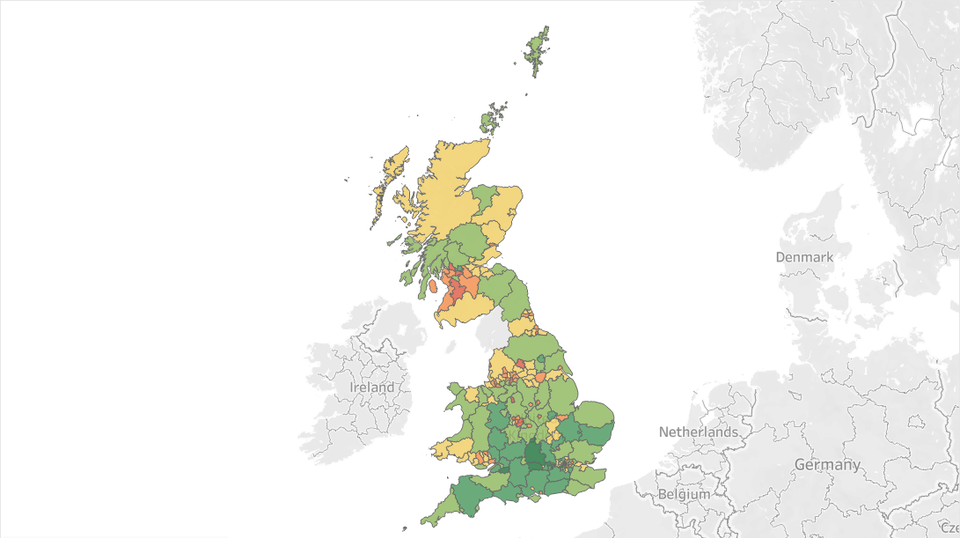

We see much the same story play out across the UK. In figures three and four below – with data for Britain only - we build a simple index to capture progress over the parliament on the core components on inclusive growth: health, income, inequality, leisure and employment.

Income inequality has fallen in many parts of the country over the last parliament with most progress being made in areas that were already wealthier with higher levels of income inequality – including Westminster, Wokingham, and Reading. However some areas – particularly across Scotland – have seen income inequality widen over the last parliament.

There is a divide in changes in life expectancy across the country with half of the country seeing life expectancy fall, and the other half of the country seeing it rise slightly. In general, areas with higher levels of disposable income have seen life expectancy rise, whereas areas with lower levels of disposable income have seen it fall.

Both parties are trying to develop a policy response to the “geography of discontent” that has been visible since the 2016 EU referendum, and which has provided the political background for three back-to-back general elections. Last year, CPP found that around half the country expects inequalities in their area will continue to rise (compared to just 10% who think it will fall); and fully 80% think the next generation will have to move in order to access better opportunities.

It’d be wrong to say that our major parties haven’t given us clues or glimpses about their wider visions for the country and our economy.

In her 2024 Mais Lecture, Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves argued that “growth in the years to come must be broad-based, inclusive, and resilient.” Beyond the ‘securonomics’ rhetoric, her pamphlet on the economy last year set out a plan for what is effectively a British form of Bidenomics to bring this vision to life, with a more active and mission-driven state reshaping investment and training to create better jobs and lower bills.

And these aspirations are not limited to one side of the political divide. Last month, Nick Timothy and Neil O’Brien, two of Theresa May’s former advisors, published a 137-page blueprint for a Conservative Economy that bears more than a passing resemblance to Labour’s emerging thinking.

Unless the Trussite wing of the Tory party regain control of the leadership, we can already make out the outlines of a cross-party economic consensus for the 2020s and 2030s. They fit with an emerging academic consensus which was set out explicitly just last week in Berlin. It begins with rejecting the old model – “growth first, inclusion second”. But what’s less clear is what comes next.

Talk is cheap. It’s easy for politicians to commit to an economy that is both bigger and offers more opportunity to more people. But delivering inclusive growth is harder. Voters are right to sceptical about politicians who promise big but can’t deliver – as the experience of the past five years makes clear.

The scale of the challenge the next government will inherit in building a more inclusive economy means we need to build up whole new parts of the state; find new ways of paying our way and paying for the public services we need; and reimagining the relationship between government and citizen. No party is grasping the nettle yet on those bigger challenges; in fact, they’re largely left unexamined, until after the election at least.

The good news is that the next Government won’t be starting from a blank piece of paper.

The view of the economy set out in the Mais Lecture and elsewhere – that public and private investment directly tackles the root causes of inequalities and low resilience – aligns with the findings of the 2016-17 Inclusive Growth Commission (the predecessor of CPP).

In our research since 2017, and through the work of our partners in the Inclusive Growth Network (IGN), we can begin to see the outlines of a truly inclusive economy. We work with fourteen places across the UK in all four nations through the network, to set the gold standard in inclusive growth, translating it from theory to practice. Leadership doesn’t stop on the boundaries of Whitehall; it takes places at all levels and in all places.

Despite the stresses and strains of a decade of austerity and disinvestment, we can see the contours of a better way of doing policy by ‘mainstreaming’ inclusive growth across organisational decision-making, strategy and delivery.

For instance, Belfast is developing a model for a consistent, cross-Council approach to inclusive growth in how they design, deliver and monitor their public investments – a model to learn from for UK-wide spending decisions.

We think this is a model that needs to be scaled up and supported across the UK. As our Fair Growth paper set out last year – and as our next Issue Briefing will elaborate on – an approach to managing our economy that simultaneously works to raise skill levels, life expectancy and close the gender gap could raise our GDP by approximately 7%.

That means looking again at UK public services, and how we deliver them. CPP’s work over the past few years has focused in particular on the case for supporting our childcare system, which we found in its current form is holding back almost a million women from entering the labour market. And we’ll need to change how we deliver core services, with places like the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham leading the way on creating – for instance – more people-centred and effective skills and job brokerage services. This has led to innovation in the delivery of employability support, enabling more people to access and stay in work by seeking opportunities to ‘nudge’ employers to offer flexible work.

Reforming our public services and shifting our mindset will help us correct some of the mistakes of our recent past. But to seize the opportunities of the future, we need to rethink the economy we could have and the state’s role in building it. We think that – with the right policies – we can have good jobs in all communities, rather than just our city centres. But we need to be hard-nosed about the trade-offs. Good things won’t always go together, as our recent work on the net zero transition and inclusive growth makes clear.

Here again there are opportunities to learn from what pioneers across the UK are already doing. Our IGN members are developing flagship projects and initiatives. Now in its fifth year, the Greater Manchester Good Employment Charter has promoted and improved employment standards across the region; and West Yorkshire is taking a groundbreaking approach to delivering inclusive growth through culture and creative industries, with the Mayor’s Screen Diversity Programme supporting young people of all backgrounds to pursue a career in film and TV.

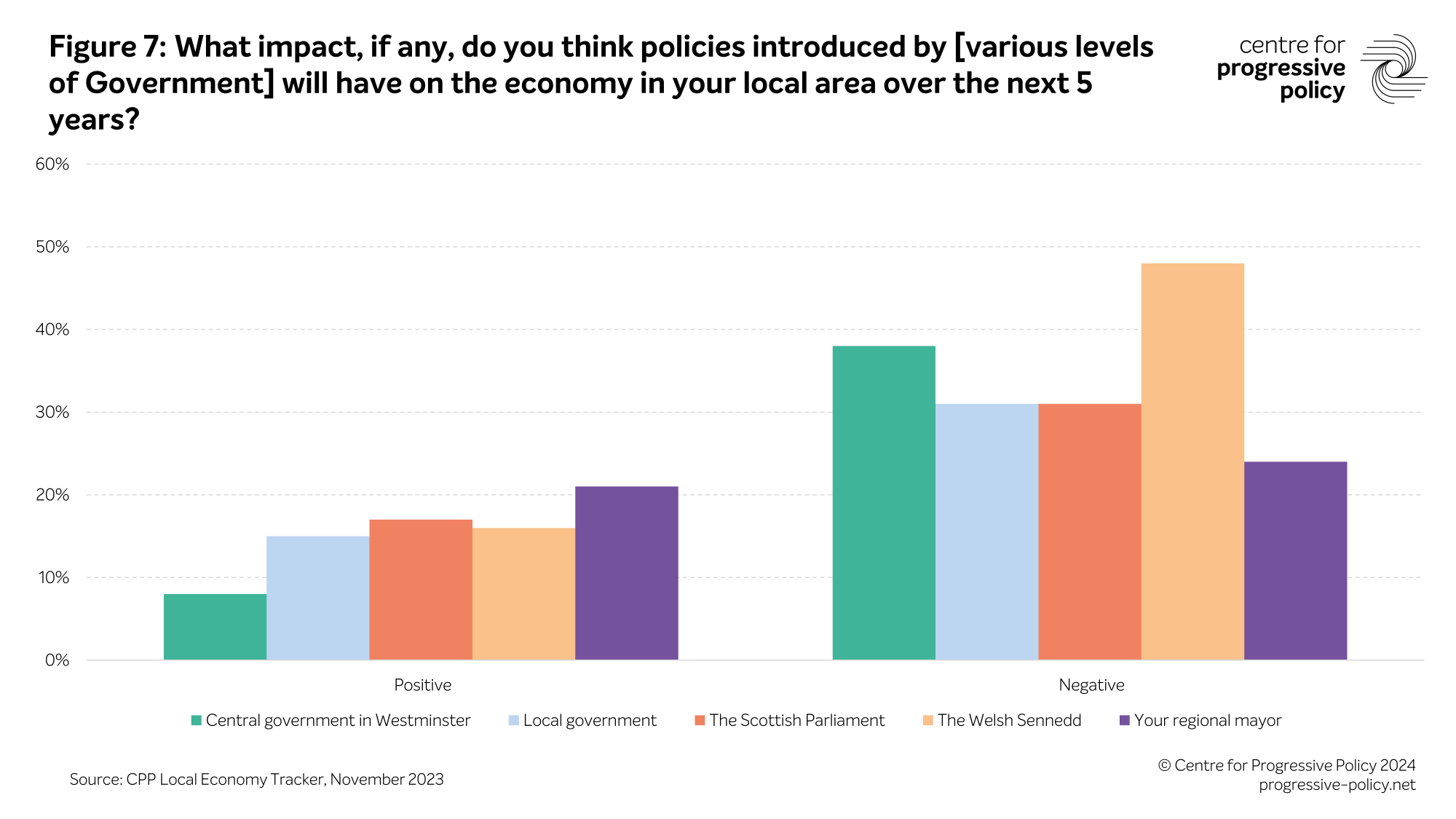

Councils and Combined Authorities are continuing to experiment with better ways of delivering inclusive growth. The next Government has an opportunity to row in behind these efforts – avoiding the “Whitehall knows best mentality” in our emerging world of devolved governance. And they will have public support if they do so. Our polling has found that the public has significantly more confidence in local leaders’ ability to drive growth than national government, pointing to devolution as a way to rebuild trust in the state:

The truth is that almost every choice the next Government makes will shape the distribution of income, wealth or opportunity in the UK. That’s the nature of political decision-making. The question is how best to think about inclusion, and how to achieve it.

Rather than offer an abstract answer to that question, CPP will use the other briefings in this general election 2024 series to ask what inclusive growth could look like in the issues the next Government can’t avoid, including:

- The size and shape of the state, looking at questions of where and how to tax and spend in the wake of last year’s Funding Fair Growth project;

- How we invest in the future and the untapped talent in our labour market today, through investment in childcare and early years;

- How we deliver “good work” and workers’ rights across the country;

- The UK’s productivity and the state of our business base. We will ask what it will take to deliver good jobs in all parts of the country after the failure of levelling up; and

- How we build a renewed public sector, capable of commanding trust and delivering growth and inclusion in all parts of the UK and at all levels – local, regional, national and in central government itself.

We shouldn’t be surprised when even sympathetic observers roll their eyes at terms like “inclusive growth”. The electorate has been promised a rebalanced economy with a fairer distribution of opportunity for several elections in a row - but we remain stuck with either rocketing inequality or shared stagnation. Why should the next parliament be any different?

Those sceptics are right to throw down the gauntlet. But if the next Government wants to still be in power by 2030, they will need to break the cycle of stagnation, and show a wide-enough coalition of people and places that they can deliver shared prosperity for the next generation.

Want to read more? Check out:

- Final Report of the Inclusive Growth Commission (2016), RSA

- Inclusive Growth in cities: a sympathetic critique (2019), Neil Lee (LSE)

- The Berlin Summit Declaration – Winning back the people (2024)

- Funding Fair Growth (2023), Centre for Progressive Policy

Want to speak? Email Dan Turner, Head of Research & Analysis, at dturner@progressive-policy.net

Sign up to our newsletter for the latest updates and insights on inclusive growth.

Notes

*An earlier version of this analysis was published on 4th June 2024 which contained a coding error. This has now been updated, changing the order of the places that saw the strongest rise and fall in the index over time.